Depression can be seen as an adaptive reaction and may force an individual to switch from the earlier modes of behavior to other unfavourable behaviors. New research from the Penn State University reveals that a unique strain of laboratory mice had behavioral, hormonal and neurochemical features that were similar to human patients with drug-resistant forms of depression. In order to introduce efficient medications for specific forms of depression mice with defect in a gene will be useful.

It was observed that functions of a protein called GABA-A receptor that is present in the brain interferes with genetic defect among depressed mice. This protein regulates the response to the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutryic acid. Anxiety disorders are related to lowered function of these receptors and not depression. This is mainly because presently available drugs that revive the GABA-A receptor are not effective as antidepressants.

“We have shown in this paper that this long-held conviction is flawed. Our research shows that the GABA-A receptor is, in fact, an important part of the brain circuitry that is not working properly in depression,” shares Bernhard Luscher, a professor of biology at Penn State.

He further quotes, “A mouse can’t tell us if it is feeling depressed, so we used a number of different kinds of tests including some new ones that we developed to gauge behavioral and hormonal changes, or phenotypes, of a type of depression that, in humans, does not respond well to some antidepressant drugs. These indicators include reduced exploration of novel or otherwise aversive environments, failure to escape from a highly stressful situation, and reduced pleasure-seeking behavior such as a reduced preference for sweet over plain water.”

Previous analyses had shown GABA-A-receptor-deficient mice to be a good model organism for studies of anxiety, which often occurs along with depression. Behavioral and hormonal symptoms of depression in the GABA-A-receptor-deficient mice were reversed by some antidepressant drugs. This was observed to bring their behavior to the level of normal wild-type mice. The normal mice did not show any reaction to the drugs

Luscher elucidates, “About 70 percent of people who are treated for depression also are treated for anxiety at some time during their lives, and the drugs that are used in people as antidepressants act not only to reduce depression but also to reduce anxiety. These facts suggest that whatever mechanism is defective in the brain is similar in both anxiety and depression. This result is expected of a mouse model that mimics depression because normal people do not seem to gain anything from taking antidepressants”.

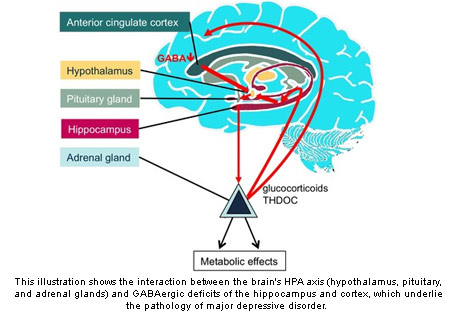

Researchers failed to understand as to why some antidepressant drugs did not assist about 30 percent of depressed patients. Doctors try one drug after the other as they don’t have a way to find out which drug works for a particular patient. The negative aspect is that it can take weeks before the drugs show any benefit. The pathology of major depressive disorder is highlighted by interaction between the brain’s HPA and GABAergic deficits of the hippocampus and cortex.

Luscher reveals, “The one that did not normalize depression-related behaviors is fluoxetine the generic name for Prozac which works on the neurotransmitter serotonin. In human patients with a type of depression called melancholic depression, fluoxetine or Prozac doesn’t work as an antidepressant but desipramine does work. These mice are a bit like those patients who don’t respond to Prozac”.

He further shares, “Our mice also showed abnormal corticosterone levels analogous to those patients who don’t respond to Prozac. In people, the cortisol level is corrected by drugs such as desipramine, and so it is in our mice. Desipramine corrects corticosterone levels in our mice but fluoxetine does not.”

Two kinds of antidepressant drugs were tested on mice and it was identified that one drug lowered symptoms of anxiety but not depression however the other drug reduced both anxiety and depression. This drug was known as desipramine that works on a different neurotransmitter, noradrenaline. These findings were significant as many patients do not respond well to Prozac. Patients who fail to respond to Prozac have augmented levels of the hormone cortisol and in mice it is called corticosterone.

Luscher elucidates, “Some research indicates that if you are born with certain types of risk factors, and something highly stressful happens in your life, such as a war experience then that event can trigger a mood disorder if you already have a risk factor. One of the many things we now want to explore is whether a slightly different strain of GABA-A-receptor-deficient mice, which are behaviorally normal but have increased levels of stress hormones, are at risk of developing depression if they experience additional excessive stress. We also want to understand in greater detail what happens in these mice biochemically to understand which genes throughout the entire genome are affected by the defect in this one gene, and the resulting depression-like brain state.”

In order to examine the role of developmental factors in the onset of depression researchers now use this model of drug-resistant depression. Researchers share behavioral symptoms are not alone produced by hormonal defect and they claim atleast not if the hormonal irregularity is present specifically in adulthood.

These findings will be published in the journal Biological Psychiatry.