The endometrium or uterine lining is seemingly the origin of adult stem cells. These cells produce uterine tissue every month as a course of the menstrual phase. Similar to other stem cells, they may also undergo division to generate other types of cells. The revelations imply that endometrial stem cells can be possibly used to create insulin-producing islet cells that exist in the pancreas. The latter could then be utilized for the progress of islet cell transplantation as a part of diabetes treatment.

“Endometrial stem cells might prove most useful for Type 1 diabetes, in which the immune system destroys the body’s own insulin-producing cells. As a result, insulin is not available to control blood glucose levels,” commented Yale Professor Hugh S. Taylor, M.D.

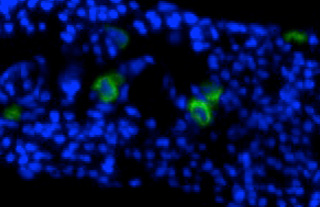

The team exposed the endometrial stem cells to cultures comprising unique energizers and growth factors. As a response to these nutrients, the endometrial stem cells supposedly imbibed the attributes of beta cells found in the pancreas that synthesize insulin. After a span of 3 weeks, following incubation, the endometrial stem cells appeared to be shaped just like beta cells and manufactured proteins normally made by beta cells. Certain cells even produced insulin.

When a meal is over, the body is touted to break down the particles into constituents like sugar glucose that then spreads in the bloodstream. As a reaction to this, beta cells secrete insulin that enables the body’s cells to absorb the transiting glucose. In this analysis, the mature stem cells were exposed to glucose which showed that like the usual beta cells, even cultured cells react by releasing insulin. Mature stem cells that made insulin were then administered into diabetic mice.

The mice seemed to have few functioning beta cells and high proportions of blood glucose. The outcomes showed that mice that did not encounter stem cell therapy presumably had high blood sugar levels, developed cataract problems and were weary. Contrarily, mice that were on the receiving end of this therapy were active and did not get cataracts. However, their blood sugar levels supposedly stayed above normal.

The team is speculating if the therapy becomes more efficient by altering the nutrient bath or elevating the dose of injected cells. The research is published in the journal Molecular Therapy.