A shot of espresso may rejuvenate you up in the morning, but the downside is that it may also increase levels of bad cholesterol due to its effects on a unique liver protein called PXR. A latest research from Rockefeller University shows that when PXR is chronically activated, the protein seems to rejigger how cholesterol is broken down in and emptied from the liver. This disturbance could possibly result in high levels of the waxy substance or worse, full-blown atherosclerosis.

Contrasting to other receptor proteins, which can identify only one or a few chemicals, PXR is known to be short for pregnane x receptor which may be able to recognize more than a hundred, including cafestrol, present in unfiltered brewed coffee, and many prescription medicines.

First author Changcheng Zhou, a research associate in Jan L. Breslow’s Laboratory of Biochemical Genetics and Metabolism at Rockefeller, says, “It’s the first time that PXR has been shown to have a direct impact on balancing cholesterol levels in the body,”

The findings of the research could have direct clinical consequences for patients consuming drugs which activate PXR. Supposedly, these drugs include the antibiotic rifampicin taken for tuberculosis treatment, the antiretroviral drug ritonavir for HIV treatment and the antiepileptic drugs carbamazipine and phenobarbital.

Zhou further elucidated that, “At the time these drugs were being developed — the antivirals, the antibiotics, anti-cancers and even herbal supplements like St. John’s Wort — their interactions with PXR weren’t known. Now patients under long-term treatment with PXR-activating drugs can be more informed about these drugs’ effects.”

When activated, PXR seems to hold on to strips of DNA and turns on genes that regulate how chemicals or drugs are metabolized and cleared from the liver. Moreover, PXR are known to reside inside the nucleus of liver cells in all animals, including humans.

Various drugs that can activate PXR appear to have been shown to raise cholesterol levels in patients. In addition, excess of the stuff in the bloodstream may possibly be a fixed risk factor for heart disease, the nation’s biggest killer. However, it seems to be unclear whether PXR could jumpstart this process.

For the purpose of the study, Zhou and Breslow were believed to have introduced a mouse-specific PXR activator called PCN into the diets of normal mice for two weeks. They found that while their levels of good cholesterol, or HDL, were not affected, their levels of bad cholesterol appear to have increased six-fold.

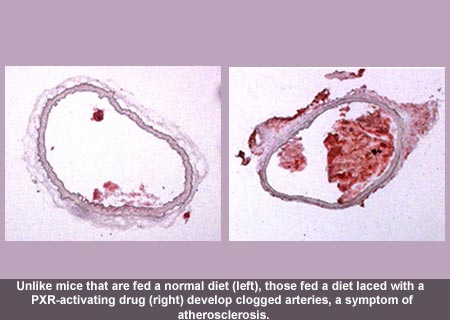

Furthermore, the researchers fed another group of mice with PCN for eight weeks and were genetically engineered to lack the protein ApoE. They found that good cholesterol of mice seems to have plummeted and they also went on to develop advanced atherosclerosis.

Apparently, several gene targets of PXR were the same for both normal mice and those lacking the ApoE protein, including a cholesterol metabolism enzyme called CYP39A1 and a transportation protein called Apo-IV. More so, a gene called CD36 was noted to be another target particularly associated with the uptake of modified bad cholesterol by certain cells which add to the buildup of artery-clogging fat.

According to Zhou, this research is only the beginning. Numerous chemicals exposed in the air are also PXR activators. So what the researchers have discovered now may not only be a heart health issue but also a public health one.