Scientists associated with this research suggest that the conclusions drawn from it focused mainly on kidney disease.

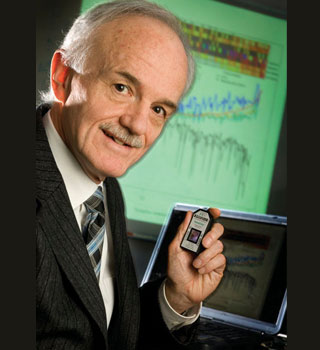

“This is a new tool to help predict which transplant patients are at risk. It offers an opportunity to develop personalized treatment plans for them,†said the lead investigator and director of the Alberta Transplant Applied Genomics Centre in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry at the University of Alberta, Philip Halloran.

He further anticipates that these findings will increase the understanding on how a kidney disease progresses. This could help comprehend various measures that can be adopted in order to bring a halt in the progression of the disease which might be a hindrance in proper functioning of the kidney. Keeping in mind that more than half of transplanted kidneys have the tendency to fail within 10 years, Peter Heeger, a nephrologist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York said that physicians need to evaluate the structure underlying transplant rejection and tolerance in humans.

The researchers observed the molecular measurements of thousands of genes present in the tissue. These tissue samples were collected from patients whose transplant had a persistent problem. The messages passed on by the genes were interpreted by an effective method which was evolved by a group of scientists at the U of A’s Alberta Transplant Applied Genomics Centre. This group was led by Hallaron and the method is now being used by medical scientists across the world. It seems to serve as a useful method in evaluating kidney transplants and increasing convenience.

Genes that are present in every cell when active are known to be capable of sending a message that is called mRNA in a process known as transcription. By identifying the present mRNA molecules, it is viable to recognize which genes are active in a cell. These messages are accessed by Halloran and his team by using ‘gene chips’. The genetic material extracted from the transplant biopsy is placed on the gene chip for further analysis and it thus measures the changes occurring with 55,000 mRNA molecules in the same time frame. This information is further fragmented into a spreadsheet which can be done with the help of powerful computers and programs capable of storing and analyzing the acquired data.

The U of A team had earlier uncovered that genes move collectively and thus reflect a disease mechanism; like cells may often fail to transfer important elements or use oxygen. As said by Halloran, the main task was to identify relevant information revealed by the molecules and he claims to have defined a preferred way to classify them.

The researchers applied this method to evaluate kidney biopsies collected from 105 patients present at the U of A and the University of Illinois who have had kidney transplants previously between 1 and 31 years ago. Computer models generated at Alberta Transplant Applied Genemics Centre, assisted researchers in determining the happenings within the tissue at the molecular level. The information revealed by the genes seemed to be unexpected with those closely related to transplant failure signaling that the tissue was making an effort to heal itself. It appeared to be much unlike the genes related to transplant rejection.

Thereafter the researchers developed a ‘risk score’ depending on various activities of this group of genes. It was observed that the more the tissue insisted to repair itself; it enhanced the chances of the transplant to fail. In order to determine the essence of this risk score it was also tested on another group of patients present at the University of Minnesota. The analysis suggested that it could be applied as a useful tool to significantly predict transplant failure more often than standard biopsy assessments.

Information provided by this research could be further developed and exploited for the benefit of the patients. Many plans are now emerging for a larger investigation that can include European and American centers. The researchers desire to use this tool to the fullest in order to evaluate kidney diseases and also other forms of transplants like the heart and liver.

The results were published online May 24 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.