Normally, amnesia is caused by damage to the hippocampi which is a pair of brain structures positioned in the depth of the temporal lobes. In spite of the condition disturbing long-term memory, such patients are apparently rather capable in remembering a phone number over a small duration of time, provided their attention is not diverted. This apparently resulted in a theory that the hippocampus supports long-term but not short-term memory. Nevertheless, the UCL study illustrates that this difference now needs to be reviewed.

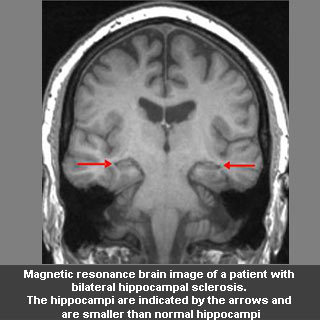

The team examined patients with a detailed type of epilepsy known as ‘temporal lobe epilepsy with bilateral hippocampal sclerosis’, which may result in noticeable dysfunction of the hippocampi. They inquired if the patients attempted to remember photographic pictures portraying normal scenes like some chairs in the living room. Their memory of the image was examined and brain activity documented via MEG (magnetoencephalography) following a small gap of just five seconds, or an extended time of 60 minutes.

The experts found that short-term memory about more comprehensive features of the scene, for instance whether the table was placed left or right of the chairs, apparently needed the synchronized movement of a system of visual and temporal brain regions, while typical short-term memory drew on an extremely diverse network. Significantly, the synchronized activity of visual and temporal brain areas was apparently disturbed in the patients suffering from hippocampal sclerosis.

Professor Emrah Duzel, UCL Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience, commented, “As we anticipated, the patients could not distinguish the studied images from new images after 60 minutes – but performed normally at five seconds. However, a striking deficit emerged even at five seconds when we asked them to recall the detailed arrangement of objects within the scenes. These findings identify two distinct short-term memory networks in the brain: one that functions independently of the hippocampus and remains intact in patients with long-term memory deficits and one that is dependent on the hippocampus and is impaired alongside long-term memory.â€

Nathan Cashdollar, UCL Institute of Neurology and first author of the paper, remarked, “Recent behavioural observations had already begun challenging the classical distinction between long-term and short-term memory which has persisted for nearly half a century.

He added that nevertheless this is the first functional and anatomical evidence showing which mechanisms are shared between short-term and long-term memory and which are independent. They also highlight that patients with impaired long-term memory have a short-term memory burden to carry in their daily life as well.

The study was published in PNAS.