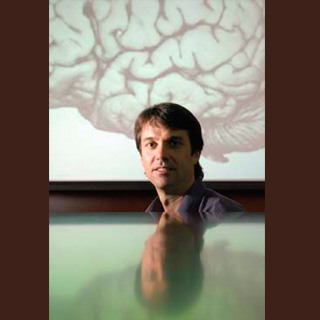

According to a latest study, the emotional centers in the brain may be able to respond much more strongly to disturbing photos if the person is unaware of what was coming. This study was discovered by UW-Madison brain researcher Jack Nitschke.

For the purpose of the study, experts made use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) on nearly 36 UW-Madison student volunteers in order to plan the reaction in two parts of the brain. The reaction inside the brain seems to be essential for emotional responding. The two parts of the brain were known as the insula and the amygdala. Apparently, this brain activity was conducted at the UW-Madison Waisman Center.

“These results have obvious relevance to our current economic times. Expectations have a dramatic impact on many aspects of our lives, including performance at work and school, interpersonal relationships and health. Expectations can alter perceptions of negative events as well as neural and emotional responses,†says Jack Nitschke, a professor of psychiatry in the UW-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health.

The students wore goggles which contained a series of pictures that were either neutral, such as a chair, or aversive, such as a badly wounded person. Before each image, the subject noticed a symbol signaling one of three things about the image. The symbol was believed to be followed with a circle in order to depict that it would be neutral. Also, an ‘X’ to signal it would be disturbing or a question mark, which seems to indicate uncertainty.

Nitschke further stated that, “This line of research is helping us understand how expectations influence our emotional responses to events.â€

The study showed much stronger neural responses to negative stimuli when the event seems to be preceded by uncertainty. The findings revealed that the insula and the amygdala both seemed to have responded more strongly to the definite aversive picture if it was preceded by a question mark. Amusingly, in those brain areas, brain was noted to respond less strongly to aversive pictures if they received a quick warning that the disturbing picture was coming. Nitschke, a psychiatrist who treats people with anxiety disorders claimed that the findings have clinical implications.

“If we can reduce people’s feelings of uncertainty, we can reduce their anxiety and their response to bad experiences. Given that uncertain expectations are paramount in clinical and sub clinical anxiety; these data suggest that more attention be paid to targeting those expectations in treatment,†elucidates Nitschke.

After the analysis, subjects were asked how often the question mark appears to have been followed by an aversive picture. The results declared that the subjects saw an equal number of neutral and aversive photos. However, approximately 75 percent of subjects were believed to have overestimated the occurrence of aversive pictures following uncertain indications. Thus the brain’s increased response to uncertainty allegedly elucidated these overestimations.

The findings of the study have been published in the journal of Cerebral Cortex.