More often than not, we all must have sometime or the other experienced our attention involuntarily being grabbed by an alarming situation even if we may be engaged in activities like reading. Like the sound of a fire alarm when we may have just started enjoying the latest chartbuster on the radio.

A new study from the Vanderbilt University seems to have an answer to exactly why this could happen. For the first time study experts reveal how are brain appears to correlate these two types of attention. It also sheds light on why surprises may blind us temporarily.

“The simple example of having your reading interrupted by a fire alarm illustrates a fundamental aspect of attention: what ultimately reaches our awareness and guides our behavior depends on the interaction between goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention,†Rene Marois, associate professor of psychology and co-author of the new study, explained. “For coherent behavior to emerge, you need these two forms of attention to be coordinated.â€

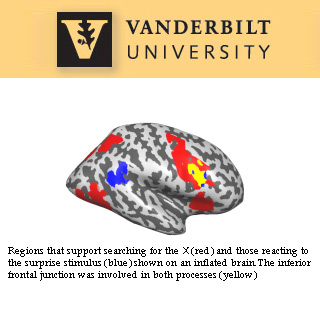

“We found a brain area, the inferior frontal junction, that may play a primary role in coordinating these two forms of attention,†added the author.

The scientists also intended to gauge what happens to us when an unexpected event holds our attention.

“We wanted to understand what caused limitations in our conscious perception when we are surprised,†Christopher Asplund, a graduate student in the Department of Psychology and primary author of the new study, remarked. “We found that when shown a surprise stimulus, we are temporarily blinded to subsequent events.â€

As part of their study, the team required participants to identify the letter ‘X’ in a stream of letters that flashed on a screen. They were asked to do this while their brain activity was being monitored using fMRI. An image of a face would abruptly interrupt the stream occasionally. Seemingly, this surprise led the subjects to completely miss the ‘X’ the first few times. This was despite the fact that they appeared to have been directly staring at the part of the screen where it was displayed. Eventually, they seemed capable of detecting it as successfully as when there weren’t any surprises.

A region of the lateral prefrontal cortex mainly the inferior frontal junction was discovered by the researchers to be involved in both the original task and in the reaction to the surprise. This was found with the help of fMRI.

“What we think might be happening is that this brain area is coordinating different attention systems – it has a response both when you are controlling your attention and when you feel as though your attention is jerked away,†Asplund commented.

Apparently surprise stimuli activate something called the orienting response. In this state the heart rate increases while the nervous system is more aroused and we appear to pay close attention to a new item in our environment. The orienting response detailed by Pavlov in dogs enables individuals to ascertain if a new item is a good thing, like as food, or a threat, such as a predator causing them to reaction accordingly.

According to the experts, a hypothesis is that we may be temporarily blinded by surprise mainly because the surprise stimulus and subsequent response takes up much of our processing ability. Asplund further shares that we probably can’t attend to everything and the inferior frontal junction is seemingly involved in this limitation in attention.

The findings support earlier work by Marois’ laboratory which uncovered the interior frontal junction to play the role of an attentional bottleneck. It was found to apparently limit our ability to multitask and attend to many things at once.

This study was published March 7, 2010, in Nature Neuroscience.