Bacterial communities seemingly have a positive impact on our health but they can also build up digestive disorders, skin diseases and obesity. Experts at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine reveal that a change in the stability between the good and the bad bacteria known to pollute the gut may be an indication of colon cancer. Findings may help to spot people with high risk and ways to modify the bacteria to avoid colon cancer.

Experts have known for long that bacteria present in the body are not mere spectators but they play a vital role in health and disease. Recently developed molecular methods help to identify and differentiate all microbial residents. Experts used these methods to examine various bacteria groups within 45 patients undergoing colonoscopies. They observed higher bacterial and greater affluence among people who have adenomas as compared to those without colorectal cancer precursors.

Senior study author Temitope Keku, PhD, study associate professor of medicine at UNC elucidates, “We think something happens to tip the balance away from the beneficial bacteria and in favor of microbes that make toxic metabolites and are detrimental to our health. By pinpointing these bacterial culprits, we can not only identify people at risk, but also suggest that they include the good bacteria in their diet. And what a great way to address colon cancer you could know your risk and lower it by eating your yogurt every day.â€

Experts observed a specific group called Proteobacteria was greater in cases as compared to controls. This is considered to be the category where E. coli and other common pathogens exist. It is not yet clear if changes in bacterial composition lead to adenomas or adenomas leads to this modified balance. In order to understand this better experts plan to conduct further analysis such as evaluate if a certain group of bacteria stimulates cancer growth in animal models. They also plan to expand the study by including 600 patients using next generation sequencing technology.

Temitope Keku reveals, “We have come a long way from the time when we didn’t know our risk factors and how they impact our chances of getting colon cancer. But now that we can look at bacteria and their role, it opens up a whole new world and gives us a better understanding of the entire gamut of factors involved in cancer diet, environment, genes, and microbes.â€

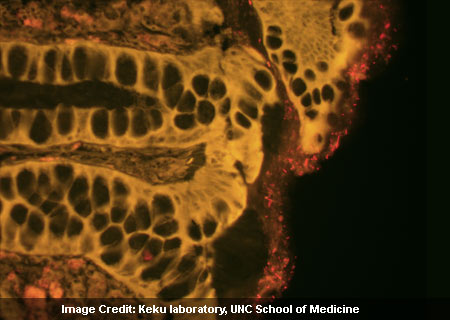

Experts aim to identify the differences in the mucosa lining present in the luminal or fecal matter that passes through the colon. This may help them observe less persistent cancer that would increase survival rates.

These findings which will appear online in the May/June 2010 issue of the journal Gut Microbes.