Scientists are discovering new things every day that seem to provide a boost to the medical field. The latest discovery pertains to a region of the brain that is apparently identified to be concerned in the initial stages of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study from Columbia University has claimed this.

Activity in this particular area of the hippocampus may assist in envisaging the beginning of the disease, providing occasions for prior diagnosis and for the development of drugs for the impediment of schizophrenia. In the study, the experts examined the brains of an approximate 18 high-risk people with ‘prodromal’ symptoms, and followed them for two years. Of those people who went on to develop first-episode psychotic disorders like schizophrenia, about 70 percent apparently had strangely high movement in the area of the hippocampus called as the CA1 subfield.

Earlier studies have supposedly recognized a more common increase in movement in the hippocampus in persistent schizophrenia. This study explains that in the initial stages of the illness, before symptoms are entirely apparent, this increased activity may be obvious only in this one subregion and could differentiate who among the high-risk people may go on to develop these disorders.

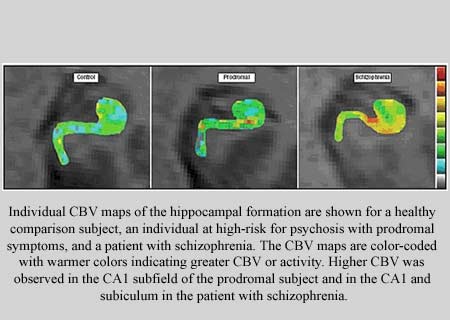

fMRI is apparently a non-invasive system that may evaluate brain metabolism, signifying what components of the brain may be active during which activities. Mapping cerebral blood volume (CBV) is supposedly a technique used in fMRI to gauge this activity and it could specify increase or decrease in metabolism.

By means of a new high-resolution function of fMRI, initiated by lead study investigator Scott A. Small, M.D., the experts first evaluated about 18 patients with schizophrenia. They were compared to 18 healthy controls and the defects in various regions of the brain of patients with schizophrenia were examined.

To study which of those areas of the brain were targeted first in patients with first-episode psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, the investigators imaged young people apparently recognized as high risk for psychosis. They were then supposedly pursued for about two years to establish diagnostic outcome.

First author Scott A. Schobel, M.D., assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, commented, “By applying this imaging technology to a population of high-risk individuals, we wanted to see if we could find an area of the brain that is selectively targeted. In comparing those high-risk individuals who developed psychosis with those who did not, we found that only the CA1 subfield was abnormal in those young people who went on to develop schizophrenia. We believe that this may give us an early snapshot of disease.”

Dr. Small, Herbert Irving Associate Professor of Neurology in the Sergievsky Center and in the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain at Columbia University Medical Center, mentioned, “What many disorders have in common is that they are all relatively invisible to conventional imaging techniques. It is crucial to be able to visualize the most affected area of the brain and to pinpoint the region that is most vulnerable. This will give us clues into the causes of the disease. Our findings could help us improve diagnosis in the preclinical stage, which is most important because it is this stage of the disease that will be most amenable to treatment.”

At present, no tests are apparently on hand to diagnose schizophrenia. Diagnosis may be mostly based on clinical symptoms after tests to rule out other likely reasons.

“These involve illusions (hearing one’s name in the wind) rather than hallucinations (hearing voices) or overvalued unusual ideas that lack the conviction of clear delusions, such as feeling suspicious of others but without a sense of being singled out or persecuted,” mnetioned Cheryl Corcoran, M.D., Irving Assistant Professor of ClinicalPsychiatry and director of the Center for Prevention and Evaluation, a prodromal research program at Columbia and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Of a usual prodromal cohort, about 35 percent may go on to develop a full-blown psychotic disorder, generally schizophrenia, in roughly 2.5 years.

Dr Small mentioned that they need to find a pattern and investigate why this area is affected first. It may be that the CA1 subfield is also driving dysfunction in other brain regions in establishing the illness.

Imaging of a bigger group and duplication of the findings may be required to explain how precise and exact this is for diagnosing preclinical schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia, as thought experts reveal is not split personality. It is a chronic, severe, and disabling brain disorder and is supposedly characterized by loss of contact with reality, hallucinations, delusions, abnormal thinking, a controlled range of emotions or unsuitable and confused behavior, social withdrawal, and reduced enthusiasm. The disease may often hit in the early adult years, and even if many people experience some recovery, many others supposedly suffer from substantial and lifelong disability. People with schizophrenia may have many issues in conducting in society and relationships.

What exactly may cause schizophrenia is not known, but existing study may propose a combination of hereditary and environmental factors. Fundamentally, however, it may be a biologic problem which could involve changes in the brain, and not supposedly caused by poor parenting or a mentally unhealthy environment.

This study was published in the issue of Archives of General Psychiatry.